A recent Harvard Business Review article, Cultural Innovation, by Douglas Holt, resonated with me on multiple levels.

A recent Harvard Business Review article, Cultural Innovation, by Douglas Holt, resonated with me on multiple levels.

- First, it’s about rethinking your category and its underlying unmet needs,

- Second, it’s all about understanding the entrenched schemas in your category and identifying hidden dissatisfiers to break them, which is the foundation for strong word-of-mouth, and,

- Third, it precisely parallels the experience I had running marketing for Equal sweetener in the early 2000’s in the face of massive Splenda spending.

While the overall piece is about creating category innovation, it’s also a great blueprint for thinking about how to position your product if you’re a challenger brand. The author lays out four key steps to aligning your brand with the unmet opportunities in a category:

1. Deconstruct the category culture – When I worked with Procter & Gamble’s Word of Mouth group, we called this “schema-busting.” Schemas are those things that we know to be true, like that chair will hold you up or it snows when it’s cold. A busted schema is what prompts word of mouth: “the chair broke when I sat on it!” Because of this, products that break category schemas are ripe for word-of-mouth.

- Dog food example from article: Big dog food companies are experts in making foods that are based on the science of nutrition.

- Equal sweetener example: The best artificial sweeteners are created through scientific innovation.. Equal brand sweetener was launched in the 1980’s by drug maker Searle and was the first new artificial sweetener created since Saccharine was developed 100 years earlier. Searle spent gobs of money promoting Equal as the latest and greatest technology.

2. Identify the Achilles’ heel – I like to think of these as hidden dissatisfiers. They’re things in the category that consumers might not necessarily like, but there is no alternative product that addresses it while also delivering all of the benefits they derive from the current options.

- Dog food example: In 2007, cats and dogs in the US died from eating food contaminated with an ingredient from China that no one knew was in their pet food: Wheat gluten.

- Equal example: There are several here: 1) The product was made by a drug company, not a food company, 2) The company was headed by Donald Rumsfeld, formerly with the Regan administration, which led to multiple conspiracy theories, and 3) It wasn’t possible to bake with at high temperature because the protein bonds that held the product together denatured with heat. This made it seem more fake/chemically processed.

3. Mine the cultural vanguard

- Dog food example: Natural dog food trend.

- Equal example: Mainstream interest in natural foods. Whole Foods went public in 1992, and Splenda launched in the US in 1999.

4. Create an ideology that challenges the Achilles’ heel

- Dog food example: Kibble is unnatural; dogs should eat real food

- Equal example: Splenda was launched with an emphasis on its supposed “realness.” Sucralose was “made from sugar so it tastes like sugar.” There was no mention of the heavy chemical processing that was required to turn the ingredients, including sugar, into something with zero calories. Their evidence: You can bake with Splenda, so it must be more real.

To paraphrase Holt’s conclusion, incumbents focus on serving the most demanding customers with the most high margin products. Given my experience with Equal and Kraft Foods, I’d argue that established companies rest on their laurels when margins and shares are high. This is why Annie’s Macaroni & Cheese was ultimately able to steal so much share from Kraft.

As for Equal, I have a colleague who worked on the brand when it was still owned by Searle/Monsanto. She said they called it “the Crustacean Era” because they were making so much money (the margins on artificial sweeteners are around 70%) that every time there was a company gathering, there would be tables full of shrimp and crab and lobster. Times were good!

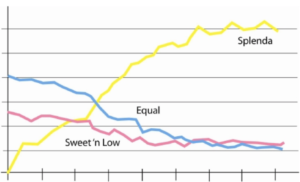

But the Equal brand got too fat and happy, to the point that they didn’t even dispute Splenda’s dubious advertising claims until it was too late and the share damage had been done. While the folks at Equal were cracking crab claws, Splenda’s US licensor, Johnson & Johnson, was busy investment spending (to the tune of 10:1) to gain the dominant share in the $1.5B category.

This article is so great because it’s a cautionary tale for large companies while it offers insight into identifying opportunities for brands willing to be challengers. It certainly resonates with me based on my past corporate experiences as well as the entrepreneurs I work with today.